- Home

- Gilbert Seldes

The Stammering Century

The Stammering Century Read online

GILBERT SELDES (1893–1970), the younger brother of famed foreign correspondent and investigative journalist George Seldes, was an influential American journalist, writer, and cultural critic, noted for championing the popular arts. Born into the Jewish agricultural community of Alliance Colony, New Jersey, to philosophical anarchist parents of Russian Jewish descent, he attended Philadelphia’s prestigious Central High School and graduated from Harvard University, where he became friends with e. e. cummings and John Dos Passos. After working as a newspaper reporter in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., and as a war correspondent in England during World War I, he joined the staff of The Dial and became the New York correspondent for T. S. Eliot’s The Criterion. In 1923, however, he went to Paris to write a book in praise of popular culture. The result, The Seven Lively Arts, appeared the following year to both considerable acclaim and criticism for its celebration of the likes of Al Jolson over John Barrymore and Charlie Chaplin over Cecil B. DeMille. In Paris, Seldes met and married Alice Wadhams Hall; the couple would have two children, Timothy, a literary agent, and Marian, a Tony Award-winning actor. Seldes later wrote columns for The Saturday Evening Post and Esquire, adapted Lysistrata and A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Broadway, made historical documentary films, wrote radio scripts, and became the first director of television for CBS and the founding dean of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. His other many books of cultural criticism and social analysis include The Years of the Locust (1932), The Movies Come from America (1937), The Great Audience (1950), and The Public Arts (1956). Seldes also published a novel, The Wings of the Eagle (1929), and, under the name Foster Johns, two books of detective stories.

GREIL MARCUS is the author of The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice, Lipstick Traces, and other books; with Werner Sollors he is the editor of A New Literary History of America. In recent years he has taught at the University of California at Berkeley, Princeton University, the New School University, and the University of Minnesota. He was born in San Francisco and lives in Oakland.

THE STAMMERING CENTURY

GILBERT SELDES

Introduction by

GREIL MARCUS

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright © 1927, 1928 by Gilbert Seldes

Introduction copyright © 2012 by Greil Marcus

All rights reserved.

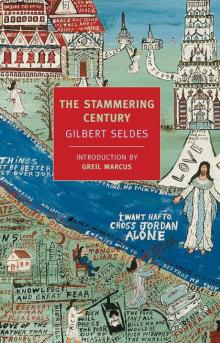

Cover image: Howard Finster, THE LORD WILL DELIVER HIS PEOPLE ACROSS JORDAN, AND MOON BECAME AS BLOOD,THER SHALL BE EARTH qUAKES (detail), Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photograph courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. / Art Resource, NY

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Seldes, Gilbert, 1893–1970.

The stammering century / by Gilbert Seldes ; introduction by Greil Marcus.

p. cm. — (New York Review Books classics)

Originally published: New York : The John Day Co., 1928.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59017-580-4 (alk. paper)

1. United States—Civilization. 2. Social reformers—United States. 3. United

States—Social conditions. 4. United States—Intellectual life. I. Title.

E169.1.S46 2012

973—dc23

2012016600

ebook ISBN: 978-1-59017-595-8

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

Biographical Notes

Title page

Copyright and More Information

Introduction

The Stammering Century

Dedication

A Note on Method

PART I

I. The Stammering Century

II. A Stormer of Heaven

III. Times of Refreshing

IV. Gasper River

V. The New Eden—

VI. —And the Old Adam

VII. Winners of Souls

VIII. A Messianic Murderer

IX. The New Soul

X. The Perfect Communist

XI. Reformer and Radical

XII. An Apostle of the Newness

XIII. Sweetness and Light

XIV. A Saint

XV. The Winsome Heart

XVI. A Moral Hijacker

XVII. Some Women Reformers

PART II

XVIII. “The Coming of the Prophets”

XIX. The Forerunners

XX. The Business of Prophecy

XXI. The Good News from Rochester

XXII. Northbound Horses

XXIII. The Path to Nothing

XXIV. Christian Science

XXV. The Kingdom of God in Chicago

XXVI. The Complex of Radicalism

Illustrations

Sources

Index

Introduction

“I CAME gradually to want to prove nothing,” Gilbert Seldes writes in his introduction to The Stammering Century. This simple sentence is a key to this galvanic, awestruck chronicle of the revivals, cults, utopian communities, and radical reform movements that under Seldes’s gaze come together as a shadow history of the United States in the nineteenth century. His “original idea,” he said, was “a timid protest against the arrogance of reformers in general”—to strip “the persecuted reformers” of their claims to sainthood or martyrdom by pious comparison: I am persecuted, Christ was crucified, therefore I am Christ. “It occurred to me,” Seldes wrote in perhaps the only really dull sentence of this book, “that a study of self-constituted saviors might serve as a check to this form of spiritual snobbery.” But Seldes found himself caught up in his story. He realized that to let his subjects speak in their own voices, to make their own kind of sense or nonsense, to give them the rope to hang themselves if that was where the story went, was a far greater thing.

The book was published in 1928; it was, Seldes wrote much later, an attempt to get to the “nature, the essential character of America”—and the nineteenth century was when America discovered itself. It was then that not only the likes of the men who signed the Declaration of Independence but people of all sorts began to talk to each other, making the great Jacksonian cacophony that Alexis de Tocqueville listened to with such wonder—though, finally, with less wonder than Seldes almost a century later.

Rolling carefully through forgotten testaments, manifestos, sermons, and prophecies—quoting at length, sometimes for pages at a time— Seldes emerged with drive, momentum, and in a hurry, leaving the reader in fright, dumfoundedness, and most of all suspense. Seldes was certain that simply to get onto the page the stories of such avatars of absolute salvation as the revivalist Charles Finney, the killer prophet Matthias, or the “Perfect Communist” John Humphrey Noyes; of camp meetings where men and women seeking union with God delivered themselves into madness; or of communities where educated people cultivated a common insanity as philosophically impregnable as it was genteel, would be to leave his readers shaking heads in disbelief—until, suddenly, their own familiar world loomed up with strange faces uttering even stranger demands, perhaps speaking in the same messianic tones the reader might have just heard and dismissed, and every politician or minister, every public voice of any sort, sounded like a doomed and beckoning figure from the past.

“I came gradually to want to prove nothing.�

� In the cadence of the sentence you can hear a New England shopkeeper returning an overcharge, in its balance one of Shakespeare’s kings admitting guilt: in the way the strength and foreshadowing of “I came” yields to the slowly declining syllables of “gradually,” hear the words almost come to a halt with the hurdles of “to want to prove,” only to come back, with the listener now barely paying attention, with the hard, blunt no of “nothing.” It is a cant-destroying voice—and it drives Seldes all across a country and a time so bent on the impossible that one can forget that the people one meets in his pages were true heirs of Franklin, Adams, Jefferson, Hamilton, Madison, walking in their footsteps, founding their own nations on a farm in Vermont, by the banks of a river in Kentucky, within the walls of a town house in New York. “There is now a certain opportunity,” wrote a founder of a new America in 1843—an America called Fruitlands, not far from Concord, Massachusetts, a new nation consisting of barely “a dozen adults and four or five children,” which lasted less than a year—“for planting a love colony which may be felt for many generations and more than felt; it may be the beginning of a state of things which shall far transcend itself.” That in a very few words catches the story told in The Stammering Century; like all of the book’s stories, it needs the anchor of Seldes’s eight words—his promise to the reader that the tale can tell itself—to keep it from floating right off into the sky.

Seldes turned thirty-five the year he published The Stammering Century. He had grown up in Alliance, New Jersey, where his father, a Russian Jewish immigrant who counted among his friends Emma Goldman and Big Bill Haywood, was a leader of an anarchist utopian community, founded in 1882, of some three hundred families. From 1920 to 1929 Seldes was the drama critic for The Dial; in 1924 he published The Seven Lively Arts, an affirmation of American popular culture that, whether people writing and talking and arguing today know it or not, has affected the American sense of self ever since. Written in Paris, “while on holiday some three thousand miles away from data, documents, and means of verification,” Seldes wrote, and “from memory,” today the book reads as a signal display of critical vision: most of those figures Seldes put forth as exemplars of the best America had to offer the world—D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, W. C. Handy, Ring Lardner, Fanny Brice and Al Jolson (sharing a chapter entitled “The Daemonic in American Theatre”), Florenz Ziegfeld, and George Herriman (his daily comic strip Krazy Kat, Seldes wrote, was the most “satisfying work of art produced in America”)—are still part of the American cultural conversation.

The book was an immediate success and celebrated on its own terms; its time-bound racism (“To anyone who inherits several thousand centuries of civilization,” Seldes wrote in a dismissal of black jazz in favor of Paul Whiteman, “none of the things the negro offers can matter unless they are apprehended by the mind as well as by the body and the spirit”) went unnoticed in respectable commentary. It was a feel-good book: it gave people permission to like what they actually liked, to be moved by what actually moved them. The Stammering Century was not a feel-good book. It was far more ambitious than The Seven Lively Arts, sprawling and crawling through the countryside and back alleys rather than striding confidently down Broadway. It shouted and whispered, and, like an invisible time-traveling journalist listening in as a century spilled its secrets, the book swiftly disappeared—“received,” as Seldes wrote in a note to a 1964 edition, “without enthusiasm except by a few reviewers who hated it.” It remains a bible, a grand genealogy, of American dreaming in action.

“This stammering century” was Horace Greeley’s pronouncement on his own era. Seldes hears two centuries at once. He hears a “fluent” mainstream composed of apostles of progress, Indian war cries, the loud talk of forty-niners, “the broad tongue of the immigrant,” anti-abolitionist mobs in Boston attacking fugitive slaves, the likes of Daniel Webster, William Cullen Bryant, and the celebrated orator Edward Everett—forgotten, as Lincoln predicted the speakers at Gettsyburg would be, for the eleven thousand words Everett offered there before Lincoln’s two hundred and seventy that followed. “Our government is in theory perfect,” Seldes quotes Everett, “and in its operation it is perfect also. Thus we have solved the great problem in human affairs.” But while the clear-tongued “were proclaiming the Gilded Age and the great promise of America,” Seldes writes, “other men were vehemently stammering out God’s curse on material progress and announcing Christ’s kingdom on earth, or the New Eden in Indiana.” They were monomaniacs, mystics, sexual reformers, death deniers, “eccentrics, fools, faddists, and madmen; but they were all concerned with the same thing: salvation,” either by a grace brought down from God or through their own actions to escape the material necessities of toil and suffering. “They looked for some end to earthly sorrows, to some perfection that could atone for our imperfect life on earth.”

Seldes sees the beginning of his story in the revival unleashed by Jonathan Edwards in Enfield, Massachusetts, in 1741, when Edwards—whom Seldes all but worships as a “merciless logician,” as subtle a prose stylist as America has ever produced, and a mystic capable of combining both logic and style into an apprehension of nature indistinguishable from sensual ecstasy—offered his congregants the sermon that has come down to us as “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Seldes’s rich and risky portrait of Edwards may go farther than Perry Miller’s complex and penetrating 1949 intellectual biography; sometimes, Seldes’s pages touch Edwards’s own “The Beauty of the World,” as indelible an America essay as any there is. It is so full of its own ecstasy that Seldes’s historical argument—that Edwards opened up a century of spiritual anarchy with “his doctrine of direct communication between man and God”—fades against his account of Edwards acting out his own play. “By making salvation the single end of man, by insisting that it was wholly God’s work, and at the same time accepting the physical signs of personal communication with the Holy Spirit, Edwards broke down the wall surrounding the ministry, and cleared the way for cults,” Seldes writes. But the drama! “Thinking of him in the dim dreary churches of colonial New England, engaged in disputation, driving grim men and starved women into frenzies of fear and hysteria, we find it hard to say the word but, in justice it must be said, he knew the essence of rapture,” Seldes writes, and then pushes on. “It is rapture without hysteria, without sham, and it never left him. When he saw Nature he recovered the emotion, because he knew that the world was the world of God . . . The golden edges of an evening cloud, the sun in his strength, the apparition of comets, the ragged rock, all exalted him.” And further: as Edwards apprehended the work of God, he saw what God must have seen as He worked.

He lowered himself infinitely, and the infinity of his lowness met, in the infinite, the Infinity of God; met, and became one with it. The two poles of man’s life, as Edwards knew them, were to be lower than the dust before God, and to know God: the ecstasy of abasement and the ecstasy of union. As he accomplished both it is possible that somewhere, in the obscure places of his heart, he felt himself God.

And that profound intoxication, Seldes goes on to show, is what Edwards really passed on. As a history, as a portrait of a phantom nation, The Stammering Century truly takes off with “Gasper River,” a composite account, drawn from the testimony of participants and observers, of an all-night camp meeting set in the Kentucky forest at the turn of the nineteenth century: Edwards’s ecstasy taken up and turned into a horror movie. As Seldes sets the scene, there is melodrama, high stakes, and most of all empathy; a sense of “You Are There” driven by Seldes willing himself into the event.

Men and women who had perhaps seen no strange face in half a year, or had been huddled together in a group of twenty or thirty for many months, suddenly found themselves in crowds of thousands . . . Before he began to speak, the preacher had already effected the release of his audience. He had set them free from loneliness and the burdensome companionship of their own troubles . . . The strange wind that had b

lown them together swayed the multitude like a field of grain. The preacher had only to put in the sickle and reap.

In a lust to touch God, to feel themselves released from sin, from the weight of their own identities, their own personalities, their own bodies, people descend into catatonic trances lasting sixteen hours or more. They tear their hair. “Others try to beat their way out of the encampment, but are paralyzed and some are torn with indecision, fearing the descent of the spirit and powerless to escape it.” Crowds are convulsed with spasmodic jerks—to the point that, according to one witness, a man snapped his neck and died. “Men and women are down on all fours growling and snapping their teeth and barking like dogs,” Seldes writes—and you can imagine that the storied description of the death, from poison, of the blues singer Robert Johnson, down on his hands and knees and barking like a dog, is less a literal account, or even a rumor, than a mandated cultural memory, a signifier, a way of saying that when one plays with the devil, as Johnson did in “Me and the Devil Blues” and “Hellhound on My Trail,” this is how that person’s fate must be described. Gospel shouters and speakers in tongues believe themselves to be vessels of the Holy Ghost, but the wall between the divine and the devil was sometimes as thin as paper: “underneath it all,” the guitarist and music historian John Fahey once said, “I hear pan pipes tooting and a cloven hoof beating time.”

In Seldes’s telling, utopian communities emerged out of the individual’s pursuit of salvation from sin—a pursuit that remains as powerful a force in American life today as it was two hundred years ago. Those communities pushed into their own wildernesses. They carried men and women farther than any could have gone on their own. The conviction that the saved were without sin moved, in a collectivity where all things, from property to children to spouses to beliefs, were to be held in common, to the doctrine that whoever was truly saved was incapable of sin—a heresy carried through Western Europe in the Middle Ages by the Brethren of the Free Spirit, revived among the Anabaptists in Münster in the sixteenth century and again by the Ranters in England a century after that. Seldes stays away from the Shakers and the Mormons—so many others had covered that ground. He takes a single cult, the Rappites of Harmony, Indiana (and then Economy, Pennsylvania—the names go by so fast), abjuring sexual intercourse, combining “a peculiar blend of communism” and “absolute despotic control” as a template, and then raises the curtain: “Over the background, the foreground, the middle-ground,” Seldes writes in a line that will echo through the nineteenth century, “lies the shadow of a single man,” who “held his position by direct order of God, and had received God’s promise.”

The Stammering Century

The Stammering Century